Survey: How Team Mood Can Impact Project Management

When strong emotions rise during a project, group members may wish they would just go away. However, ignoring the group’s feelings may be detrimental to project success: Research has shown that “hurricane employees” who barrage a team with negative emotion can affect productivity 30 to 40 percent. Conversely, happy teams may experience up to a 12 percent rise in productivity.

Software Advice recently conducted an online survey of 1,552 adults to reveal whether people observed negative emotions at work, and whether this impacted their personal mood and performance. We also interviewed Professors of Management Dr. Sigal Barsade of the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and Dr. Donald Gibson of Fairfield University, who study the impact of mood on productivity; their insights are integrated into the findings below.

Vast Majority Say Co-Workers Exhibit Negative Emotions

First, we asked our survey respondents how often they perceive a co-worker’s negative emotions. As it turns out, the majority of respondents (84 percent) had witnessed a co-worker exhibiting emotions such as anger or frustration with varying levels of frequency.

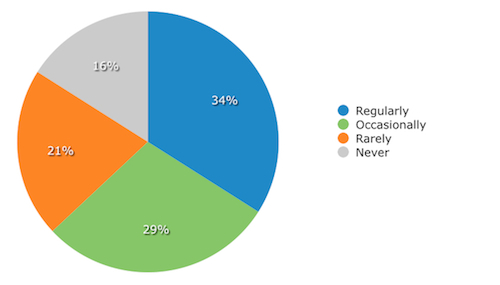

Of those respondents who had experienced co-workers’ negative emotions, over one-third (34 percent) said they “regularly” witnessed it, 29 percent said they witnessed it “occasionally” and 21 percent said they “rarely” experienced it. A smaller number of respondents (16 percent) said they “never” witnessed co-workers displaying negative emotion.

Frequency of Perceived Negative Emotions From Co-Workers

As Barsade explains, “emotional contagion” is when group members “catch” each others’ emotions like they would a virus. The process starts with the innate tendency to mimic the expressions and gestures of those around us—a form of mimicry that triggers an internal, physiological response.

“When we make the facial expressions and gestures,” says Barsade, “we actually start to feel the emotion.”

Since emotion spreads between individuals, a whole project team can be impacted by just one employee’s negative “affect” (a term, synonymous with “emotion,” used in the field of organizational behavior).

And this impact is tangible; according to Barsade, “[Emotions] don’t just influence workplace attitudes. They also influence behavior and performance.”

Majority Can Sense Anger, Frustration From Managers

In our survey, we also wanted to see whether managers’ emotions were noted by team members. While reported less often than experiences with co-workers, a solid majority (73 percent) noted that they had witnessed a manager exhibiting negative emotions with varying degrees of frequency.

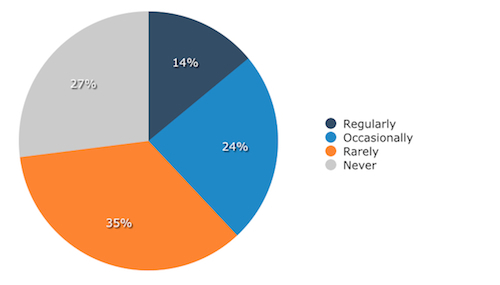

Of respondents who had witnessed a manager’s negative emotions, 14 percent indicated they “regularly” witnessed it, 24 percent said they witnessed it “occasionally” and 35 percent said they “rarely” witnessed it. Twenty-seven percent said they “never” witnessed their managers displaying negative emotion.

Frequency of Perceived Negative Emotions From Managers

For those in a leadership role—such as project managers—the stakes may be higher for displaying strong emotion. Gibson says team members tend to pick up on the mood of their leader. Since this typically happens unconsciously, managers may not be aware that group members are mirroring back their own feelings.

Barsade says leaders can also attempt to redirect those displaying negative affect by modeling positive emotions non-verbally, such as smiling and making an effort to “look encouraging.”

Mood, Productivity Diminished by Negative Emotions

Most respondents reported that, when faced with the negative emotions of themselves or others in the workplace, both their mood and productivity would be negatively impacted (75 percent) to varying degrees. The remaining 25 percent claimed they were not at all impacted by experiencing negative emotions.

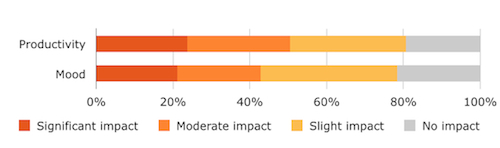

Drilling deeper, we compared the impact on productivity versus on mood for those who said they would be impacted. Our data suggest a correlation between the two. Reports of “significant impact” to mood and productivity, for example, are within three points of each other: 21 percent said their mood would be significantly impacted, while 24 percent said their productivity would be significantly impacted. Reports of a “moderate impact” were similarly close, with 22 percent reporting their mood would be moderately impacted, versus 27 percent for productivity.

Impact of Negative Emotions on Team Members

The largest number of respondents said they would be slightly impacted by negative emotions in the workplace, with 36 percent reporting a “slight impact” to mood and 30 percent reporting this for productivity. The remaining said they wouldn’t be impacted at all: 22 percent reported “no impact” to mood and 19 percent said the same for productivity.

Gibson says that that the emotional tendencies members bring to the group—upbeat, neutral or pessimistic—combine to create a “group mood.” Thus, he notes, people with similar dispositions generally work better together.

“What is not good is if you have four positive people, and one negative person,” says Gibson. “That can be a very dysfunctional team, because that [negative] person is so dissimilar.” He adds that when assembling a team, managers should consider members’ emotional tendencies, not just their technical expertise.

Moreover, says Barsade, organizations should be cognizant that the more positive the affect of a team, the more productive the team tends to be overall.

“Positive mood really helps with thinking and creativity … If you’re kind of down, and you’re surrounded by people who are really up, that can actually help your performance,” she says.

Many Take Personal Responsibility for Negative Emotions

As you can see, unmitigated negative emotions in the workplace can wreak havoc on productivity, and positive emotions can promote success. But who is responsible for addressing negative emotions?

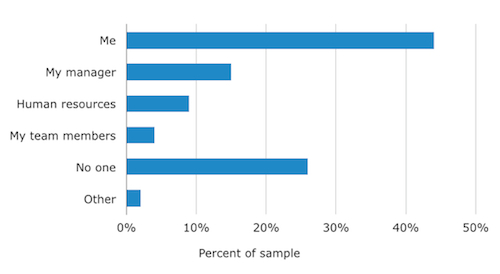

Fifteen percent said their manager should be responsible for addressing negative emotions, and 9 percent thought human resources should address the situation. A small number (4 percent) reported that fellow team members were responsible, while 2 percent answered “other”—including a few who noted that the person who was the source of negative emotion was the one responsible for addressing it.

Party Most Responsible for Addressing Team Emotions

It turns out that the majority of respondents took personal responsibility: 44 percent selected “I am responsible” when asked who should address the negative emotions they experience in the workplace. Interestingly, though, the second most common response (26 percent) was that negative emotions shouldn’t be addressed by anyone at all.

It turns out that the majority of respondents took personal responsibility: 44 percent selected “I am responsible” when asked who should address the negative emotions they experience in the workplace. Interestingly, though, the second most common response (26 percent) was that negative emotions shouldn’t be addressed by anyone at all.

The issue of perceived responsibility makes it trickier to effectively address group emotion. Since the science of emotional contagion suggests that people’s moods are subconsciously affected by the emotions of others, it may not be entirely possible for individuals to take responsibility for themselves.

Moreover, while team members may take too much personal responsibility, managers may sometimes take too little. Though 15 percent think managers should be responsible, Barsade says that managers themselves tend to see managing group emotions as outside their job description. However, research has shown that teams respond positively to a manager who wields emotional intelligence—meaning effectively reading emotions and knowing when to take necessary action.

“Managers who read their subordinate’s emotions are rated more highly by their subordinates,” says Barsade, “and are rated as more transformational leaders.”

Finally, there are those who don’t think anyone should address workplace emotion. People may feel emotions don’t belong at work, or may be uncomfortable confronting feelings. Whatever the case, the reality is that negative emotions impact productivity—so team members and managers alike stand to benefit from gaining deeper emotional intelligence. Luckily, there are some specific things managers can do to tackle the issue of negative workplace emotions.

Managers Play Significant Role in Influencing Emotion

How can project managers be responsive to the emotional life of their team? Here, Gibson and Barsade have a few suggestions:

Track Your Team’s Emotions. Gibson says that one tool used in organizational behavior is the PANAS (Positive and Negative Affect Schedule), which helps measure a group’s mood by taking an average of members’ positive and negative emotions. While the manual shows a complex method for finding this, there are softwares today to automate the process. The project management tool Niko Niko, for example, allows team members to enter their real-time mood, then calculates the average. (Barsade notes that she’s currently working with this company on primary research).

Promote Emotional Intelligence. Workplaces have traditionally addressed interpersonal dynamics using personality tests such as Meyers-Briggs (though some have debated this test’s efficacy). But there is also a wide range of resources available that specifically promote emotional intelligence. For example, team members and leaders can discover how well they read the emotions of others through the Emotional Intelligence quiz from Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center, and learn how to improve this skill using the readings and assessments available through the Consortium for Research on Emotional Intelligence in Organizations.

Be Attentive to Anger. “Anger can be a positive emotion in the sense that if someone is angry about something, usually it’s a problem [in the workplace],” says Gibson. Managers should try to respond to problems revealed by anger, especially if the team member(s) in question are commonly in a good mood. However, Gibson also says managers should be attentive to the situational context surrounding each expression of anger, as anger can also signal a hostile individual with chronic negative emotions.

Have One-on-One Conversations. For morale issues impacting the whole group, says Barsade, managers may need to check in with individual team members, and try to determine whether the cause of an emotion is work-related.

“Just because you see an emotion doesn’t mean you know what caused that emotion,” Barsade says. “[You should have] a sensitive and empathetic conversation about what’s going on … and what can be done about it.”

Do you see emotional intelligence as an important factor for your team? Leave a comment below to let us know how you deal with strong emotions in the workplace.

Methodology

To find the data in this report, we administered an online survey of five questions, each of which was answered by at least 385 unique respondents—1,552 respondents total—taken from a random sample of people within the United States. We worded the questions to ensure that each respondent fully understood their meaning and the topic at hand.